“It was once a source of shame, but now I say it proudly: bad English is my heritage. I share a literacy lineage with writers who make the unmastering of English their rallying cry — who queer it, twerk it, hack it, Calibanize it, other it by hijacking English and warping it to a fugitive tongue. To other English is to make audible the imperial power sewn into the language, to slit English open so its dark histories slide out.”

-Cathy Park Hong, “Bad English,” Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning

Raise your hand if you’re racialized and a white person has said to you some version of, your English is really good. Or maybe this less friendly but no-less-patronizing sentiment: learn to speak English.

Black and Indigenous people and people of colour are constantly policed and spoken down to when it comes to how we speak or write.

Here’s an example that has stuck with me over the years. Back in 2011, I was waiting in a rush line for a screening of The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 and reading a review of the movie in NOW Magazine. Susan G. Cole had written:

“To give the film some shape, contemporary artists including Erykah Badu and a super-articulate Talib Kweli express their debt to the period.”

I remember thinking that something was off about that “super articulate.” But I didn’t have the words for it then.

I do now. It’s patronizing, belittling, presumptuous. It’s racist. It’s cringe.

I wonder how surprised Cole was to find out a Black man could be well-spoken.

Reminds me of how a white male former coworker of mine would every so often tell me, unprompted, “you’re a good writer” (read: “you’re actually a good writer”). Dude, no one asked you.

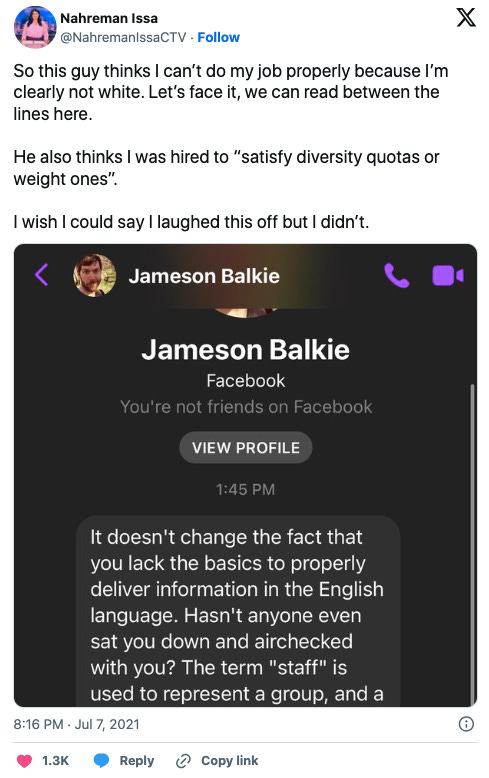

To give a more current example, here’s something I saw on Twitter recently:

This shit is infuriating and happens all the time. White people love to claim authority and put racialized folks “in our place.” There are too many Jameson Balkies taking up too much space, offering up unsolicited commentary on our proficiency with English instead of engaging with the substance of what we say.

I’m really tired of it, and lately I’ve been thinking more about who I write for and how I can decentre whiteness in my own work.

It’s certainly a work in progress; I have a lot to learn and unlearn.

In my childhood home, the primary languages were Vietnamese and English. I would also hear snippets of Cantonese and Teochew, which my parents sometimes used when speaking with certain family members or friends.

In hindsight I wish I had embraced and appreciated being immersed in my mother tongue. I’m sad to say that I’ve lost a lot of my Vietnamese. Thankfully there’s nothing stopping me now from picking it back up again. But growing up, I didn’t care to preserve my fluency because I was trying to assimilate. Ever since I can remember I’ve been working to conquer the English language so that it doesn’t conquer me — so that I could be “good enough” in the eyes of white people, or maybe even beat them at their own game.

I’m done with that. I’m no longer adhering to white notions of what is respectable or proper or worthy. Because whiteness is no longer the standard I aspire to.

As a friend of mine once said, white people need to get over themselves. True then, true now.